His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands. -W. Faulkner

Recently, I’ve been quite busy working on a script narrative for a computer game that I’ve been working on for nearly 2 years now. It’s not the same game that I started out with. Indeed, I have had several major changes in direction, each turn became a personal revelation why the other idea just didn’t work for me.

One could look and say that I was fickle. Ultimately, I couldn’t concern myself with it whether it was true or not. For what is ‘fickle’ if only an external point of view used to categorise, and thus predict future behaviour? Why should I, of all people, predict my future behaviour?

One thing that I’ve learned is that the creative process is a process of thinking and feeling. Thinking and feeling bounce off each other and influence each other in kind. From thinking and feeling, we come upon that collection of intuitions that we may call instinct.

In writing, of which I know little about, I have been informed that there are types of writers who are plotters, and those that are pantsers. I’ve discovered that I’m a little of both.

In animation, of which I know much about, there are two animation methods called pose-to-pose, and straight-ahead. As an animator, I don’t work exclusively with one method over another. These methods are not techniques per se, but the only two ways of thinking about technique. Hence, as an animator, you are use both principles in order to find multifarious methods suited for the works that you want to do.

Whether you take concepts such as these strictly or loosely, the most important thing for the artist is knowing how and why these concepts are applied. I call this the Grey Area, because there is no right or wrong, only why something is working or not.

The Grey Area is like the Grey Matter — our brain — where any external concept floating out there in the world can plop down and relax. It is our little private room where we can do anything we want with these concepts, and no one has to know about them. Privacy is key, because privacy is what makes it special to oneself and potentially to the rest of your external world. As far as philosophy and analysis is concerned, I confine myself to these coarse principles of creativity. I’m happy to let ambiguous concepts mutate and evolve in the Grey Area.

Unfortunately, because of that loose creative disposition, I become irritated by over-analytical people. Out there abounds articles of a scientific bent which seek to ‘optimise audience-user engagement’ and ‘define and measure suspense (anxiety) in terms of durability’. Presumptuous titles adorn most of these presumptuous articles, and sometimes follow a template such as: “How Science is Helping Art…”, ‘Art’ being things brought on by the creative process, I would assume.

The life that gives breath to these articles is a superciliousness of these business-minded scribblers who use the authority of science to convince us of what they think the bottom line art is supposed to be. Go scrounge a few measurements, researches, testimonies, call it science if you will; but what was it that caused them to think that art was made to catalyze ‘unconscious involuntary responses‘, or ‘meet audience expectation’? If art had to exercise techniques in manipulation, and to some degree it has to, why does this seem like the overriding function of art? Why does a biological and psychological research into, say, the ‘fear-anxiety process’ infer that such stimulus must be pandered to at all?

The idea that science is serving the purposes of art is one of willful ignorance: even if scientific researches don’t objectively presume to understand or even define art, but only to observe its effects, why are the results of its conclusions always encourage ‘scientifically minded’ people to presume that artists need to act on these effects? Let’s be honest and perceive that science does not conduct its business to serve art. Instead, its very insistence seeks to bring itself above art by defining it, by saying, “I know you better than you know yourself. This is what you really need.”

And that’s the point when I say, no, I don’t. You can tell me what makes me cry in a movie, but you can’t tell me if I should be crying at all. You can push all my buttons to make me keep from pressing the stop button on this crappy movie for a few seconds longer, but you can’t tell me that it’s truly worthwhile watching. And if we, as artists, keep conversing in the thoughtless language of statistics and obsessive yet irrelevant analysis, pretty soon that’s all ‘Art’ is going to become

(If it isn’t already.)

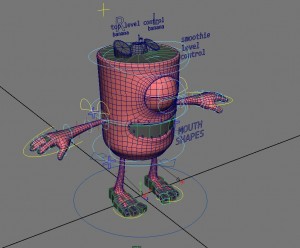

Then, it was a simple matter of comping, using masks, the mouth cavity and eyes, and the rest of the limbs.

Then, it was a simple matter of comping, using masks, the mouth cavity and eyes, and the rest of the limbs.