I had started out as a freelance in my previous company, and then a year later, I became a permanent staff as a CG supervisor. A CG supervisor’s responsibilities may encompass many things. Or, inversely, may encompass only a narrow field. This depends on the company’s expectations from the role and the person. As such, some write certain things on paper, but are not carried out in reality, and vice-versa.

As a technical person in a supervisory role, I naturally supervised everything I had competent skills in. This meant everything in CG post-production, whether it would be as high-level as a pipeline development, or low-level as switching out a heat sinks from defective computers. This is just my nature. I like fixing, and designing things as well. There were some things that I initially didn’t always look forward to, like production shoots, but it was my job. And in the end, I learned to like it as much as a computer geek possibly can.

Through the intervening 5 years, the role remained as broad as I was. There was no need to do less work. In Sporty Drive, I had taken more responsibilities than before, but no more than a CG supervisor of my expectations would have. This would be the only project in 5 years that I can confidently assert that gave me a sufficient level of satisfaction after its completion. But from then on, as if on the downward phase of a sine wave, it became a challenge of enduring the tedium of the advertising world.

Tokyo Ghoul was the last major project I worked on in that studio. And I mention this because it serves as an end reference point for my role as CG supervisor just before I left. We hired a new great TD, originally from Weta, and both worked — in tandem with the main studio in Japan — on some shots for Ghoul. Our major task was rigging, though we also did some animation, too. Although I had been usually the one to work on rigging in the past, the studio execs and producer wanted to leverage our new TD’s expertise and occupational history to impress our Japanese counterparts, so all of the rigging work was assigned to him.

I was left to become a visual effects producer of sorts. I helped write the final visual effects breakdown; since our work was technical in nature, I wrote documentation and emails explaining the technical concepts to a non-technical Japanese translator: what problems we were having, the details of what we need, what the rigs are meant to do, etc. I created video tutorials for workflow suggestions (that sometimes had nothing to do with rigging, but simply a knowledge exchange between CG artists), and for explaining the rigs we were delivering. It echoed my Lifeway CG teaching days.

(I also did some animation: when we couldn’t afford to get animators in, I took over and animated a few shots in the end.)

You can say that my role was largely educational and social. It was challenging and it was important as well. I’m aware of that, and I’m fine with it. But this isn’t the sort of thing that I’d been wishing for. In fact, this was certainly a step in the wrong way, and a step that I had been forced to make gradually over the years.

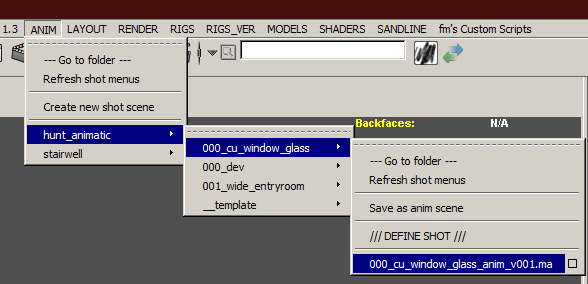

The execs do not have any sense (tactically or strategically) for technicalities of CG production, so they habitually nod their heads in feigned consonance whenever I relate anything related to technology or software. Thus it becomes a difficult proposition to build anything of substance in an environment where pipeline is only just a word bandied about creative directors who want to sound cool among production people. It’s not real enough for execs; it’s not as real as clients’ whims, it’s not as real as the debates of the philosophy of creativity that I used to hear in our open-space office, it’s not even as real as promised money.

I am not exaggerating when I say that though I had been coding the studio’s pipeline for 5 years, the execs have assumed that I don’t actually code, and perhaps they think I just download plugins and scripts. Anyone who truly knows my development work will probably laugh at that bit of irony. And I’m laughing a bit, too. (Of course, never mind the 10 odd years prior of doing code; to some that’s ancient history.)

Perhaps they lacked confidence in my professional pedigree, or they didn’t know enough to understand any other aspiration apart from theirs. Perhaps, perhaps. Either way, I saw the trajectory of where I’d end up, and if I wouldn’t be out of a job due to redundancy, I would have been out of my mind in boredom.

So, in the end, when an opportunity presented itself to do a bit of original coding related to Iray, Janus, and LightWave, I took on a contract, despite its short term.

I think there’s a point when many factors for quitting converge. But some seem so charged with emphatic resonance that you’d think that was the primary reason for changing your job (or your life). People might say they hated working with so-and-so, or got paid peanuts, or felt no respect from others, or the workplace was stressful. But all of them helped to make it worse, until at one point, not any one of those factors is going to be enough to make it better. When the bad stuff accumulates, it hardens after a time. Then, even if they worked on getting new tables, lamps, decors, heaters, hardware, software, or whatever to make it seem that they’re addressing issues, everything wrong has accumulated to the point none of it matters. Because none of them, by themselves, matter anyway. As one the execs — an example of irony if I ever saw one — used to pontificate: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. And so truly, it is: when the parts are faulty, the whole is more faulty than the parts.