I went one of the local libraries the other day with the intent of spending my morning there reading, and the rest of the afternoon drawing. As I moved closer to the book shelves, for one reason or another, I remained in the graphic novels area – a general genre of books that I have very little interest in. I still like some comic books: Asterix, Calvin & Hobbes, Far Side, Peanuts, TinTin, B.C., etc; I grew up with these. Thanks to my brother I was exposed to more serious minded comics like The Light and Darkness War, whose style and tone was, to a young teenager, something like a wide awakening – a baptism of imagination, if you’d like. The panels were watercoloured, the lines were thick-thin, and the prose was poetic enough for me at the time to appreciate the authors’ collaborative voice.

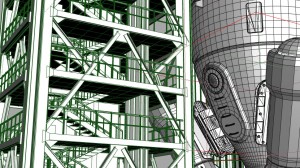

I took some of this with me in my days in a fine arts college – my course was actually more oriented to graphic arts – and cultivated the inspiration as much as an under-achieving art student could. But diving into the labour force after college essentially marked the end of my adventures with serious graphic novels: comics which portray violence – often extreme – and gore, sex and explicit language. My foray into computer graphics turned my attention away from drawn stories.

It was only recently that, after longing to re-imagine myself and reassess my goals, I wanted to go back to basics and start drawing in earnest again, after ten years of professional CG work. And that’s where I found myself in front of the graphic novels area staring at a copy of DMZ. It featured mercenaries, and it described a dystopian landscape – I sneered on finding out that the story was set in NYC. NYC is over-mentioned, you see: ’nuff said.

I read the whole book. And despite the clumsiness of lines, the inexpert description of form, and even the cliche of its language, I appreciated it mainly because it touched on subjects that I had swirling in my brain: guns-for-hire and wastelands of worlds. When I had finished I put it back on the shelf.

I wasn’t satisified: I wanted another to feed my mind. I laid eyes on one book. I wasn’t fully interested in the cover, so I scanned the shelf a bit more. I spent five minutes flipping through pages, then my eyes passed on the book again. I thought, “Hey, look, there’s a tired-looking Afghan with an AK47”. So, on account of sighting an AK47 I picked up The Photographer and started the story that would prove to be the closest thing to a second awakening.

The book is not a miraculous work. It’s not the most outstanding piece of literature I’ve read: I’ve been impacted more by other books, far deeper, and far longer. But this, being a graphic novel, it impacted me far more than any graphic novel I’ve flipped across.

As I read, it felt it difficult not to compare it with the recently-read DMZ. I became acutely aware of how dissatisfied I was with the other book, and how much more refined and expertly Emmanuel Guibert, the illustrator and visual director of The Photographer, had drawn, and – more surprisingly – had written the story of Didier Lefèvre. He had interspersed his comics with Didier’s photographs as he told of Didier’s travels to Afghanistan. Because the illustrations realistically depict people in a simplified (read: masterfully economical) style, the black-and-white photographs jolt you to the palpable sense that the story is really non-fiction. It doesn’t just fill in the blanks between the discrepancy that a photo-essay’s pictorial gaps suggests; it puts in a much more lucid level of storytelling.

Despite the fact that the subject matter was about doctors and a photographer, and that the only shot fired in anger was from an “asshole ‘muj'”, The Photographer thoroughly impressed, and more importantly, inspired me. In the CG field there is so much emphasis on detail, which involves real-world fidelity be it in photographic, or otherwise just physical terms. If it isn’t that, then it’s about resolving our work methods to conform to some pipeline: yet another detail to abide by. But within The Photographer, I found none of that. In the first place, the illustrations were minimalist, and yet I found excellent form posture, action, and human expression; detail was only necessary when it was necessary. In the second, the photographs were not used because they were photographic in quality, but because they, as photographs, told their part of the story. In the third place, the style of telling was uniquely individual: it wasn’t like one of those monthly high-profile, run-of-the-mill animated-feature-films (where almost every animated character motions with his hands and eyebrows the same (freakin’) way). The writing was powerful, brutally honest: honest enough that in two parts in the story it made me sad enough to tear up. A comic book has never had that effect, and I never thought it could have.

The Photographer’s impact on me as a reader and as an artist has caused me to re-evaluate what I am really about as a creative person. I would like to think I was a real artist, but I know that I am just a mercenary CG man with good artisan and technical skills. I’m not sure how much of being a professional contributes to creativity, but I can say that this book has forced me to confront the numerous habits and rules I have adopted as a professional. It is easy enough to say to think outside the square, than to realise that you are the square.